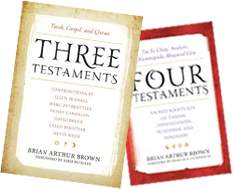

The illustrations for Three Testaments are mainly black and white “wood-cut” engravings of biblical material not covered in the Torah text, maps related to the context of Jesus’ ministry, and Islamic calligraphy, mostly positioned on the usual blank “verso” (left) pages at the end of chapters, or on the blank partial pages on the “recto” side. They will add charm as well as information to this volume.

In August and September I blogged some thoughts about the “Ground Zero Mosque” controversy and the aborted threat to burn the Quran to reflect on the timeliness of our book, since timing is to publishing what location is to real estate. In reply, I heard from some of you about the current exhibition at the New York Public Library, illustrating our society’s current fascination with the texts about which we are writing. Jennifer Palin is a minister of my denomination in Toronto, and Ward Kaiser, the author who introduced the Peters Projection World Map to North America in A New View of the World, loves the New York scene. I thank them both for forwarding the information I want to share this month. None of these particular images will appear in Three Testaments, but they testify to the importance of such art in our production, and the New York Public Library is also supplying the illustrations for our text. If the following excerp from a New York Times review intrigues you, you might want to visit the New York Public Library site (highlighted below) where you can scroll down to click on the article and see the stunning illustrations currently on exhibit. I encourage you to do so. I hope to visit this exhibition at the library myself after Christmas when I am in New York to complete the permissions for illustrations in our book. Otherwise, negotiations with prospective publishers continues, as does the work of our various contributors.

The sweep of the new exhibition at the New York Public Library — “Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam” — is stunning. It stretches from a Bible found in a monastery in coastal Brittany that was sacked by the Vikings in the year 917, to a 1904 lithograph showing the original Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue. It encompasses both an elaborately decorated book of 20th-century Coptic Christian readings and a modest 19th-century printing of the Gospels in the African language Grebo. There are Korans, with pages that shimmer with gold leaf and elegant calligraphy, and a 13th-century Pentateuch from Jerusalem, written in script used by Samaritans who traced their origins to the ancient Northern Kingdom of Israel.

The similarity in religious traditions is also emphasized in an accompanying miniature exhibition in an adjacent gallery, called “Scriptorium” — the “place where scribes write and illuminate books or scrolls.” Here are samples of parchment (skins of goats, sheep and deer); several kinds of traditional paper (including ahar — paper coated with alum and egg whites); display cases with the sources of pigments like pomegranate peel or dried insects; and videos on the creation of pens and inks and manuscripts. So much is shared in these three faiths. But the distinctions are also important and tend to be too aggressively minimized. For example: the biblical story of Abraham welcoming the three messengers who announce that his aged wife will give birth is pictured in an elegant image from a 15th-century New Testament “Gospel According to Luke,” from Muscovy. The haloed visitors actually anticipate the Magi bringing gifts, and, as the label points out, give a presentiment of the doctrine of the Trinity.

Or again, in the Koran, Moses and Mary, the mother of Jesus, are both treated as prophets, but they are reinterpreted as heralds of what is yet to come. In fact, because Christianity developed out of Judaism, and Islam grew out of both, similarities and allusions are also the markers of great differences. Each religion aggressively reinterpreted its predecessors, accepting its sacred texts but radically altering their implications and meanings. And each predecessor religion, in turn, opposed attempts to treat it as a prelude to something greater.