The foreword is yet to be completed by a person who can express the essence of the book, and it should be someone with a high enough profile to help sell it. I have had a lot of good advice on this and suggestions that we might invite Hans Küng, the Aga Khan, Harold Kushner, David Frost or Rowan Williams. Any of them might have been willing and each of them would have been appropriate, but the choice has fallen on Amir Hussain, the Editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion.

As perhaps the leading interfaith commentator in America at least, Amir is a Professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, who describes himself as “a Muslim Canadian teaching in an American Catholic university.” I have seen the first draft of his piece and it is both insightful and succinct. Because we have a couple dozen new readers of this blog during the countdown to publication, the first half of Professor Hussain’s foreword might make a good introduction to the work for them, and I know that others of you will enjoy it too. The rest will follow in due course.

Foreword by Amir Hussain

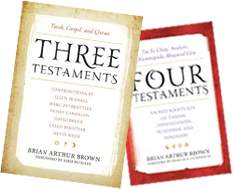

The book that you hold in your hands is revolutionary. It presents together the texts of the Torah, Gospels, and Qur’an, inviting the reader to examine the interdependence of the Scriptures that are central to Jews, Christians and Muslims. That shared presentation in and of itself gives Three Testaments its name and makes it extraordinary. What makes it revolutionary are the connections that Brian Arthur Brown and the other contributors to this volume make between these three great traditions.

In speaking about itself as it often does, the Qur’an says (3:7) that those whose knowledge is sound will say that: “We have faith that what is in it is all from God. But only those who have wisdom understand”. This book provides both the wisdom and the understanding.

To show the deep connections in our religious history, my mentor, Professor Wilfred Cantwell Smith began one of his books, Towards a World Theology, with the story of Leo Tolstoy, his Confession from 1879, published in 1884. How many of you are familiar with Tolstoy and the story of his “conversion” from a worldly life to a life of ascetic service? The story that converted him was the story of Barlaam (the hermit) and Josaphat (the Indian prince). In the story, the Indian prince Josaphat is converted from a life worldly power to the search for moral and spiritual truths by Barlaam, a Sinai desert monk. Tolstoy learned the story from the Russian Orthodox Church. However, it was not a Russian story, as the Russian Church got it from the Byzantine Church. But it was not a Byzantine story, either, as it came to the Byzantine Church from the Muslims. But the story did not originate with Muslims, as Muslims in Central Asia learned it from Manichees. And in the end, finally, it was not a Manichean story, as the Manichees got it from Buddhists. The tale of Barlaam and Josaphat is in fact a story of the Buddha. Bodhisattva becomes “Bodasaf” in Manichee, “Josaphat” in later tellings of the tale.

However, Wilfred’s genius was not in simply pointing to the history of this story, but to how it moved forward in time. Those who know Tolstoy know that he was an influence on a young Indian lawyer, Mahatma Gandhi, who founded Tolstoy farm in South Africa in 1910. And those that know Gandhi know that the story does not end with him. Gandhi was an influence on a young African American minister, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. The story shows that we are connected to each other, both forwards and backwards in time.

We see that connection when we study our scriptures. Our best scholarly evidence tells us that the Torah was written in its final form during the Babylonian Exile. We know how the Zoroastrian tradition, present in Babylon during the exile, influenced the Bible. In this book, Brian Brown credibly re-establishes the traditional understanding that Jewish monotheism predates that of Zoroaster, despite popular and esoteric predilections placing him thousands of years earlier. Moses or one of the neighbouring Hebrew prophets may even have been a source of inspiration for Zoroaster, whose dates we now believe to be early seventh century BCE, though, at a later time, Zoroastrians helped the Jews in their midst to recognize God himself as the only “Redeemer” of Israel. Brown then shows how possible exposure to Zoroastrianism may have been a revelation to Jesus about his messianic destiny, not only to restore the Davidic kingdom, according to his spiritual understanding of it, but also to be the “Savior” of the whole world. Finally, Brian Brown presents the Qur’an’s self-understanding as confirming both the Jewish monotheistic heritage and the messiahship of Jesus. He shows the Quran to confirm Scriptures in addition to those of the Hebrew and Christian communities, (notably Zoroastrian), by employing a traditional Islamic perspective that may be a welcome affirmation for Muslims and helpfully insightful for Jews and Christians in particular.

Ellen Frankel and Marc Brettler present their portrayals of the resolute dedication of Jews to their covenant relationship with God and with each other, as well as certain inconsistencies in the various expressions of that heritage since at least the time of Moses. Henry Carrigan and David Bruce describe the devotional aspect of the stories of Jesus in Christian tradition and the intricacies associated with the texts of the Christian Scriptures. Laleh Bakhtiar and Nevin Reda bring the cutting edges of both classical and progressive Islamic scholarship to bear on challenges associated with presenting the Quran in the context of twenty first century investigations.

(To be continued)